Overcoming Space Constraints in Exploit Development

A Guide to Staging Shellcode in Limited Buffer Scenarios

The Constraint Scenario

You have successfully identified a vulnerability. You have fuzzed the application, calculated the offset, and confirmed you can overwrite the Instruction Pointer (EIP). You are technically in control of the machine.

You attempt to inject your standard reverse shell payload,typically around 350 to 400 bytes,only to find that the exploit fails immediately.

The Problem: Limited Buffer Space

The vulnerable input field (the buffer you are overflowing) is too small. Perhaps it only accepts 50 bytes of data before the return address. After consuming 4 bytes for the EIP overwrite, you are left with a mere 46 bytes of usable space. Your 350-byte shellcode is being truncated, causing the application to crash without executing your payload.

Does this render the vulnerability unexploitable? Not at all. It simply requires a change in strategy.

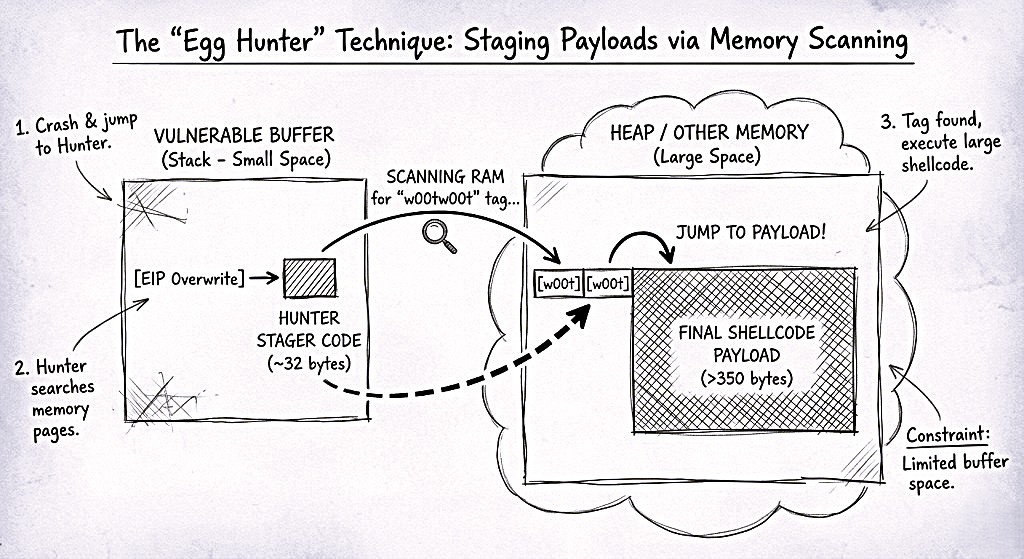

The Concept: Hunter and Prey

In this scenario, we likely have ample memory available elsewhere in the application’s address space. We just cannot jump directly to it because we do not know its precise address.

To solve this, we split the exploit into two distinct stages:

- The Egg (The Payload): We place our large, final shellcode in a different, non-vulnerable part of the application that allows for larger inputs (e.g., a “User-Agent” header or a “Password” field). We prefix this payload with a unique marker, or “tag.”

- The Hunter (The Stager): We place a very small, highly optimized piece of assembly code (approximately 32 bytes) into the small, vulnerable buffer where we control execution.

The Execution Flow:

- We trigger the overflow and jump execution to the Hunter.

- The Hunter acts as a search engine for the system’s memory. It systematically scans the process’s Random Access Memory (RAM) page by page.

- It checks every memory address for our specific tag.

- If the tag is found, the Hunter redirects execution flow to the code immediately following the tag,our reverse shell.

The Anatomy of an Egg

To facilitate this search, the payload must be easily identifiable. We utilize a 4-byte tag repeated twice (8 bytes total) to ensure uniqueness and prevent false positives.

Standard Tag: w00t (Hex: 77303074)

Final Payload Layout in the “Safe” Memory Area: [w00t] + [w00t] + [Reverse Shell Code]

Why the Double Tag? The Hunter code itself must contain the string w00t to know what it is looking for. If the Hunter scanned for a single instance of w00t, it would likely find itself in memory first, enter an infinite loop, and crash the exploit. By searching for w00tw00t (contiguous), we ensure it ignores its own code and finds the actual payload.

The Hunter Code

You rarely need to write this assembly from scratch. The security researcher Skape published the definitive Egg Hunter assembly, and it remains the industry standard.

The logic operates by utilizing system calls to verify if a memory page is readable before attempting to read it, preventing access violations that would crash the program.

Pseudo-Assembly Logic:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

loop_inc_page:

OR DX, 0xFFF ; Fast forward to the end of the current memory page (4096 bytes)

loop_inc_address:

INC EDX ; Increment to check the next memory address

PUSH EDX ; Save the current address context

PUSH 0x43 ; Prepare the system call (access() check)

POP EAX ; Load the syscall number

INT 0x2E ; Execute the system call (kernel interrupt)

CMP AL, 0x5 ; Check for E_ACCESS violation (0x5)

JE loop_inc_page ; If unreadable, skip to the next page entirely

check_for_egg:

MOV EAX, 0x74303077 ; Load our tag 'w00t' into the register

MOV EDI, EDX ; Prepare the address for comparison

SCASD ; Compare memory at EDI with EAX

JNZ loop_inc_address; If no match, increment and try next byte

SCASD ; Check the NEXT 4 bytes. Is it 'w00t' again?

JNZ loop_inc_address; If no match, increment and try next byte

found_it:

JMP EDI ; Tag found. Jump to the shellcode immediately following it.

Note: The specific syscalls used (INT 0x2E) are specific to Windows environments. Linux egg hunters use different syscall vectors, but the algorithmic logic remains identical.

Implementation Guide (OSCP Methodology)

You can practice this technique on standard vulnerable applications like VulnServer or SLMail.

- Identify the Constraint: Confirm that the buffer following the EIP overwrite is insufficient for a full payload (e.g., less than 50 bytes).

- Generate the Hunter: Use tools like Metasploit or Mona within immunity Debugger to generate the hex code for the hunter.

msf-egghunter -f python -e w00t

- Place the Egg: Identify a secondary input field in the application that accommodates larger data.

- Example: If the

USERcommand crashes the app but has a small buffer, check thePASScommand. IfPASSallows 500 bytes, inject your Egg (Tag + Shellcode) there. It will remain resident in memory.

- Example: If the

- Send the Hunter: Exploit the vulnerable

USERcommand. Overwrite the EIP to jump to your 32-byte Hunter code. - Execution: The application may freeze momentarily while the CPU scans memory. Once the Hunter locates the tag in the

PASSvariable, it triggers the jump, and you obtain your shell.

Why This Technique Matters

Mastering the Egg Hunter demonstrates a shift from simple tool usage to actual exploit development. It teaches a fundamental lesson: Constraints are often illusions.

- Not enough space? Use an Egg Hunter.

- Bad characters breaking your code? Use an Encoder.

- Stack not executable? Use Return Oriented Programming (ROP).

In exploit development, you do not always need to fit the “bomb” in the mailbox; sometimes, you just need to fit the map that leads to it.