Malware Propagation Lifecycle

An Overview on malware propagation techniques, covering infection vectors, lateral movement, and persistence strategies.

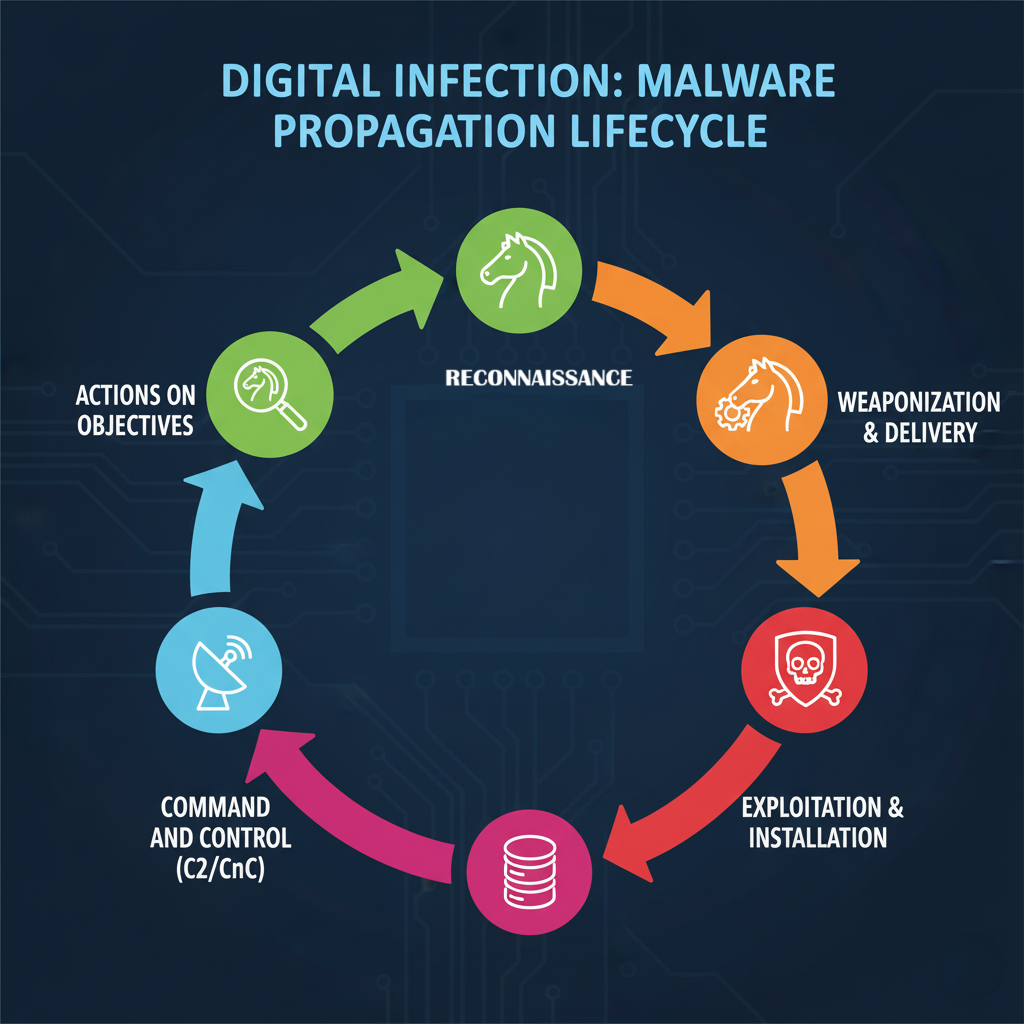

For CEH and OSCP candidates, mastering the Malware Propagation Lifecycle is essential. This blueprint maps the adversary’s journey from initial idea to final objective. It’s the critical sequence of events security professionals must learn to recognize, exploit, and defend against. Let’s examine the crucial stages that dictate an attack’s success.

Phase 1: Reconnaissance (The Stalker)

This is the planning and information-gathering stage. The malware hasn’t been deployed yet, but the attacker is actively selecting and surveying the target.

- Goal: Gather as much intelligence as possible to identify weak points.

- Techniques:

- Passive Reconnaissance: OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence) like checking LinkedIn for employee emails, corporate website for network details, or DNS records.

- Active Reconnaissance: Port scanning (e.g., Nmap), running vulnerability scanners against public-facing assets, and sometimes social engineering calls to map internal roles.

- CEH/OSCP Relevance: This is where you, as a penetration tester, begin—mapping the network and identifying the Attack Surface.

Phase 2: Weaponization & Delivery (The Package)

Once the target is selected and a vulnerability is identified, the attacker crafts their weapon and plans its delivery.

- Weaponization: Creating or selecting a malicious payload (the malware) and coupling it with an exploit. This often involves obfuscation or crypting the code to evade signature-based detection.

- Delivery: Getting the weaponized payload to the victim. Common vectors include:

- Phishing/Spear Phishing: Malicious email attachments (e.g., weaponized Microsoft Office documents with macro payloads).

- Exploiting Internet-Facing Services: Targeting vulnerable web servers or VPNs.

- Drive-by Downloads: Compromising a legitimate website to automatically serve malware to visitors.

- Analogy: The delivery is the equivalent of slipping a Trojan Horse past the city’s guards—it needs to look benign.

Phase 3: Exploitation & Installation (The Breach)

This is the point of initial compromise. The malware’s code is executed, and a foothold is established.

- Exploitation: The delivery mechanism successfully triggers the exploit, taking advantage of a system or application vulnerability (e.g., a buffer overflow in a legacy service or a zero-day in a browser). This grants the attacker initial, limited access.

- Installation (Establishing Foothold): The payload downloads and executes the primary malware, often a backdoor or a Remote Access Trojan (RAT). This is crucial for Persistence, ensuring the attacker can regain access even if the system is rebooted. It often involves creating a new service, registry key, or cron job.

- OSCP Relevance: Think about post-exploitation—this is where your meterpreter session lands, and you immediately focus on persistence.

Phase 4: Command and Control (C2/CnC) (Calling Home)

The compromised system is now connected to the attacker’s remote infrastructure.

- Goal: Create a covert communication channel for the attacker to issue commands and receive stolen data.

- Mechanism: The installed malware beacons out to an attacker-controlled C2 server (often over common ports like 80/443 to blend in with normal web traffic). This is often done using encrypted protocols or Domain Fronting to evade Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS).

- The Worm Example: A worm differentiates here by using the C2 channel or local network protocols (like SMB) to search and automatically compromise other vulnerable hosts on the internal network, dramatically accelerating propagation.

Phase 5: Actions on Objectives (The Mission)

The final, and most damaging, stage where the attacker achieves their ultimate goal.

- Privilege Escalation: Moving from the initial compromised user’s low-level privileges (e.g., a standard employee) to a higher level (e.g.,

NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEMor a Domain Admin). Common techniques include kernel exploits, misconfigured services, or credential dumping (e.g., Mimikatz). - Internal Reconnaissance & Lateral Movement: Mapping the internal network, pivoting to other high-value systems, and spreading the infection.

- Exfiltration/Impact: The actual “mission.” This could be:

- Data Exfiltration: Stealing sensitive files (PII, IP).

- System Disruption: Launching a DDoS attack from a botnet.

- Ransomware: Encrypting systems and demanding payment (e.g., the WannaCry outbreak).

Case Study: The Worm Propagation (WannaCry)

- Recon: The attackers knew the widespread use of the SMB (Server Message Block) protocol on Windows networks.

- Weaponization: They used the NSA exploit, EternalBlue, bundled with a self-replicating ransomware payload.

- Delivery/Exploitation: It was delivered via a general infection vector (e.g., a backdoor from a previous breach) but its propagation was primarily through a self-propagating worm that immediately exploited the unpatched SMB vulnerability (MS17-010) on any internal or external host it could reach, with NO USER INTERACTION required.

- C2 & Action: Once a system was exploited, the worm installed the WannaCry ransomware, which encrypted files and initiated C2 communication for key management and further lateral spreading.

Conclusion: Breaking the Chain

As an aspiring ethical hacker, your job is to find the weak links in this chain. You need to identify and secure the common choke points:

- Delivery: Strong email filtering and user awareness training.

- Exploitation: Regular and timely patching (e.g., the MS17-010 fix).

- C2: Network segmentation, egress filtering, and robust monitoring for suspicious outbound traffic.

- Privilege Escalation: Least privilege principle and removing unnecessary local administrator rights.

Mastering this lifecycle is not just memorization—it’s developing the mindset of the attacker to better defend and test systems.