LINUX File permissions Explained

A Brief guide on managing file permissions using "CHMOD"

File permissions are core to the security model used by Linux systems. They determine who can access files and directories on a system and how. This article provides an overview of Linux file permissions, how they work, and how to change them.

How do you view Linux file permissions?

- The ls command along with its -l (for long listing) option will show you metadata about your Linux files, including the permissions set on the file.

1

2

3

4

5

$ ls -l

drwxr-xr-x. 4 root root 68 Jun 13 20:25 tuned

-rw-r--r--. 1 root root 4017 Feb 24 2022 vimrc

In this example, you see two different listings. The first field of the ls -l output is a group of metadata that includes the permissions on each file. Here are the components of the vimrc listing:

- File type: -

- Permission settings: rw-r–r–

- Extended attributes: dot (.)

- User owner: root

- Group owner: root

The fields “File type” and “Extended attributes” are outside the scope of this article, but in the featured output above, the vimrc file is a normal file, which is file type - (that is, no special type).

The tuned listing is for a d, or directory, type file. There are other file types as well, but these two are the most common. Available attributes are dependent on the filesystem format that the files are stored on.

How do you read file permissions?

This article is about the permission settings on a file. The interesting permissions from the vimrc listing are:

1

rw-r--r–

This string is actually an expression of three different sets of permissions:

1

2

3

rw-

r--

r--

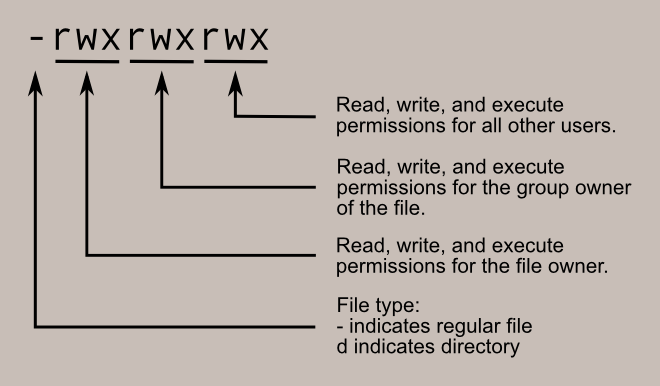

The first set of permissions applies to the owner of the file. The second set of permissions applies to the user group that owns the file. The third set of permissions is generally referred to as “others.” All Linux files belong to an owner and a group.

When permissions and users are represented by letters, that is called symbolic mode. For users, u stands for user owner, g for group owner, and o for others. For permissions, r for read, w for write, and x for execute.

When the system is looking at a file’s permissions to determine what information to provide you when you interact with a file, it runs through a series of checks:

- It first checks to see whether you are the user that owns the file. If so, then you are granted the user owner’s permissions, and no further checks will be completed.

- If you are not the user that owns the file, next your group membership is validated to see whether you belong to the group that matches the group owner of the file. If so, then you’re covered under the group owner field of permissions, and no further checks will be made.

- “Others” permissions are applied when the account interacting with the file is neither the user owner nor in the group that owns the files. Or, to put it another way, the three fields are mutually exclusive: You can not be covered under more than one of the fields of permission settings on a file.

What are these octal values?

When Linux file permissions are represented by numbers, it’s called numeric mode. In numeric mode, a three-digit value represents specific file permissions (for example, 744.) These are called octal values. The first digit is for owner permissions, the second digit is for group permissions, and the third is for other users. Each permission has a numeric value assigned to it:

- r (read): 4

- w (write): 2

- x (execute): 1

In the permission value 744, the first digit corresponds to the user, the second digit to the group, and the third digit to others. By adding up the value of each user classification, you can find the file permissions.

For example, a file might have read, write, and execute permissions for its owner, and only read permission for all other users. That looks like this:

- Owner: rwx = 4+2+1 = 7

- Group: r– = 4+0+0 = 4

- Others: r– = 4+0+0 = 4

The results produce the three-digit value 744.

What do Linux file permissions actually do?

I’ve talked about how to view file permissions, who they apply to, and how to read what permissions are enabled or disabled. But what do these permissions actually do in practice?

Read (r)

Read permission is used to access the file’s contents. You can use a tool like cat or less on the file to display the file contents. You could also use a text editor like Vi or view on the file to display the contents of the file. Read permission is required to make copies of a file, because you need to access the file’s contents to make a duplicate of it.

Write (w)

Write permission allows you to modify or change the contents of a file. Write permission also allows you to use the redirect or append operators in the shell (> or ») to change the contents of a file. Without write permission, changes to the file’s contents are not permitted.

Execute (x)

Execute permission allows you to execute the contents of a file. Typically, executables would be things like commands or compiled binary applications. However, execute permission also allows someone to run Bash shell scripts, Python programs, and a variety of interpreted languages.

How do directory permissions work?

Directory file types are indicated with d. Conceptually, permissions operate the same way, but directories interpret these operations differently.

Read (r)

Like regular files, this permission allows you to read the contents of the directory. However, that means that you can view the contents (or files) stored within the directory. This permission is required to have things like the ls command work.

Write (w)

As with regular files, this allows someone to modify the contents of the directory. When you are changing the contents of the directory, you are either adding files to the directory or removing files from the directory. As such, you must have write permission on a directory to move (mv) or remove (rm) files from it. You also need write permission to create new files (using touch or a file-redirect operator) or copy (cp) files into the directory.

Execute (x)

This permission is very different on directories compared to files. Essentially, you can think of it as providing access to the directory. Having execute permission on a directory authorizes you to look at extended information on files in the directory (using ls -l, for instance) but also allows you to change your working directory (using cd) or pass through this directory on your way to a subdirectory underneath.

Lacking execute permission on a directory can limit the other permissions in interesting ways. For example, how can you add a new file to a directory (by leveraging the write permission) if you can’t access the directory’s metadata to store the information for a new, additional file? You cannot. It is for this reason that directory-type files generally offer execute permission to one or more of the user owner, group owner, or others.

How do you modify Linux file permissions?

You can modify file and directory permissions with the chmod command, which stands for “change mode.” To change file permissions in numeric mode, you enter chmod and the octal value you desire, such as 744, alongside the file name. To change file permissions in symbolic mode, you enter a user class and the permissions you want to grant them next to the file name.

You can modify file and directory permissions with the chmod command, which stands for “change mode.” To change file permissions in numeric mode, you enter chmod and the octal value you desire, such as 744, alongside the file name. To change file permissions in symbolic mode, you enter a user class and the permissions you want to grant them next to the file name.

For example:

1

2

$ chmod ug+rwx example.txt

$ chmod o+r example2.txt

This grants read, write, and execute for the user and group, and only read for others. In symbolic mode, chmod u represents permissions for the user owner, chmod g represents other users in the file’s group, chmod o represents other users not in the file’s group. For all users, use chmod a.

Maybe you want to change the user owner itself. You can do that with the chown command. Similarly, the chgrp command can be used to change the group ownership of a file.

What are special file permissions?

Special permissions are available for files and directories and provide additional privileges over the standard permission sets that have been covered.

- SUID is the special permission for the user access level and always executes as the user who owns the file, no matter who is passing the command.

- SGID allows a file to be executed as the group owner of the file; a file created in the directory has its group ownership set to the directory owner. This is helpful for directories used collaboratively among different members of a group because all members can access and execute new files.

The “sticky bit” is a directory-level special permission that restricts file deletion, meaning only the file owner can remove a file within the directory.

Wrapping up

Understanding Linux file permissions (how to find them, read them, and change them) is an important part of maintaining and securing your systems. I could explain only basic points here(ofc this topic is slightly less interesting) and if you are willing to learn more about this, refer this goated book which has all linux essentials you need.